|

Generating music by computer and "What makes a good tune?" |

Recent addition : An original analysis of good tunes to find why they sound so appealing and memorable.

|

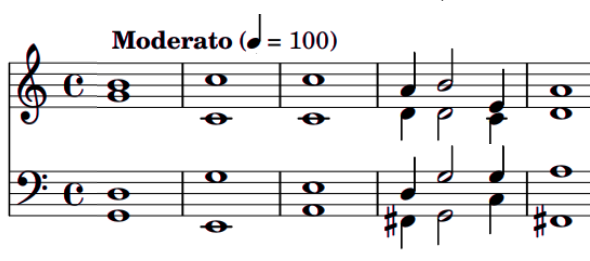

Today powerful computers programmed with artificial intelligence are routinely carrying out brain-work -- thinking, judging, selecting, creating -- which we humans once thought only we could do. There are several programs which produce music in different styles. Article: "A suite of programs to Simulate Elementary Aspects of Construction of Tonal Music " This page outlines my own attempts to write a suite of programs to carry out the basic carpentry tasks in inventing music. It does not used artificial intelligence; instead the algorithms are based on 'rules' to create the sequences of chords, vocal lines and melodic decoration in common practice in the 18th century -- Bach and Haydn's time -- as set out in the many textbooks on musical theory. I started writing these many years ago using the BBC Basic language and have continued to use it. My methods are not sophisticated and the results are modest. As an examples, here is an organ prelude in an antique style My approach has been to build up a short piece of music (or section of a longer piece) in stages. First a list is created denoting, in the usual Roman numerals notation, a sequence of triads which make musical sense -- for example I, IV, I, V, VI, II, V, I. This lst is converted into a piece in crude 3-part or 4-part harmony in a major or minor key, and in 2, 3 or 4 beats per bar as the user specifies. The shapes of the 4 voices are guided by curves effectively drawn across the staves by the user. An further program cleans up this harmonisation by removing bad parallels between voices and ensuring that each chord has all three notes of the triad sounding. Yet a further program will insert sequences of parallel chords called linear intervallic patterns. The output is a series of block chords sounding rather like an antique hymn tune (chorale). Here is an example in a minor key, which appears as Figure 56 in the article. The subsequent programs in the suite elaborate this hymn tune in various ways, again under some control by the user, though most of the changes are made automatically using decision algorthims and some random numbers. One basic elaboration is to add passing notes. When the above hymn tune has had some passing notes randomly added into each voice, it typically sounds like this (see Figure 57 in the article0. An alternative elaboration of the basic hymn tune uses suspended notes and accented passing notes on the first neat of a bar (called appoggiaturas) to give a different feel to the piece, as illustrated here. One further type of decoration is to replace some of the remaining longer notes with a patterns of shorter neighbouring (auxiliary) notes. These are notes which differ from the given harmony note by only one scale step up or down. The user can control how many such decorations are inserted -- it is quite possible to go well over the top and produce a musical jumble, though the algorithm largely prevents clashing discords. Here is another version of the organ prelude quoted above, though played on a different organ. The difference is in the random way the longer notes have been embellished with auxiliary notes. The production of the sounds is largely automated, since I use the free downloadable programs Lilypond and GrandOrgue. My programs save the created voice lines in a code which denotes the pitch and duration of each note. This is converted by another program in the suite into a Lilypond file (www.lilypond.org) which, when run, generates both a pdf file of the engraved sheet music and a MIDI file. GrandOrgue, as its name implies, is a virtual pipe organ which can be played from a MIDI keyboard as well as from a loaded MIDI file. It too is free and is supported by free sampled sounds from several real organs, all available through www.sourceforge.net. I am most grateful to the authors of this free software -- a wonderful resource. I used the sample sounds of Polish and other European organ on the web site of Piotr Grabowski. I do not intend to publish the suite of programs themselves because they are not in a sufficiently tidy and robust state for other users. The article here, however, gives an account of the algorithms and the thinking behind them. These are the sections in the article, in pdf format here: Section 2: gives an overview of the essential ideas behind Western tonal music. Section 3: presents a considerable body of data on the frequencies of occurrence of various chords and chord sequences. Section 4: describes how I have used this data in Program 1, which generates a string of triads in either the major or minor mode, labelled only by Roman numerals, in an order which makes musical sense. A sub-section discusses modulation to the dominant and relative minor keys. Section 5: is about voice-leading within one melodic line; it describes Program 2 to generate a canto fermo melodic line in notes of equal duration. Program converts the output of the note-generating programs into a Lilypond file from which it is engraved as a musical score and converted to sound as a MIDI file. Program 4 is a development of Program 2 in which the shape of the melodic line is controlled by a user-defined mathematical curve. Section 6: describes stages in the development of Program 5 which makes a first attempt at 4-part SATB harmony. The approach is to lay four voice-line guide curves across the sequence of triads generated by Program 1 Once preliminary measures to prevent parallel unisons, octaves and fifths have been put in place, the results are fair but not perfect. Section 7: is a diversion from computer codes to a discussion of several aspects of rhythm and the development of melody with rhythmic interest. Subsections examine agogic accent in polyphonic music, cadences, musical motifs, compound melody and sequences, and also the textures used in 18th and 19th century piano writing. This section effectively defines the challenges and sets out the agenda for developing algorithms. Section 8: outlines Program 6 with examples. This is a first steps towards imposing form on the sequences of triads.. On the assumption that a piece is constructed from a number of 4-bar blocks, Program 6 searches for chord pairs which could become cadences at suitable positions through the sequence, allocates a number of beats according to a user-selected time signature, and then allocates the other triads to beats between the cadences. The output can be realised as a piece of music using Program 5. Section 9: returns to the challenge of producing 'correct' 4- and 3-part harmonisation of a sequence of triads. It builds upon Program 1, Programs 6 and 5, applied in that order, to generate a crude first harmonisation. Program 7 attempts automatically to correct the faults in this first version by completing all triads with root, 3rd and 5th, and to correct parallel unisons, fifths and octaves. Section 10: is about inserting so-called linear intervallic patterns, a type of musical sequence, into a piece. Section 11 deals with inserting passing notes. Section 12 describes Program 10 which elaborates voices lines by allocating rhythmic and patterns of shorter neighbouring notes to each long note. Section 13 is about the several ways of combining two or more voice lines into one -- arpeggiation, pedal notes, compound melody, etc. Section 14: gives some examples of short pieces created using the suite of programs as tools. (to be completed) I come back to the point that these programs deal only in the elementary procedures in the carpentry of musical composition. What is lacking is that overall intelligent, tasteful sense of style and integrity which gives a piece a definite character. It reminds us just how rare really great music actually is. Perhaps it is best to regard the 'music' produced by these programs as possible starting material for a talented human musician to correct, elaborate and rewrite -- a spur to innovation, but certainly not an end in itself. Article: "A suite of programs to Simulate Elementary Aspects of Construction of Tonal Music " Supporting article: Fitting mathematical curves to the typical shapes ofd musical phrases. |